Manhattan, 2016

Targeted is an interactive video installation that aims to make the invisible, visceral by making the experience of being targeted felt by everyone, not just the usual suspects.

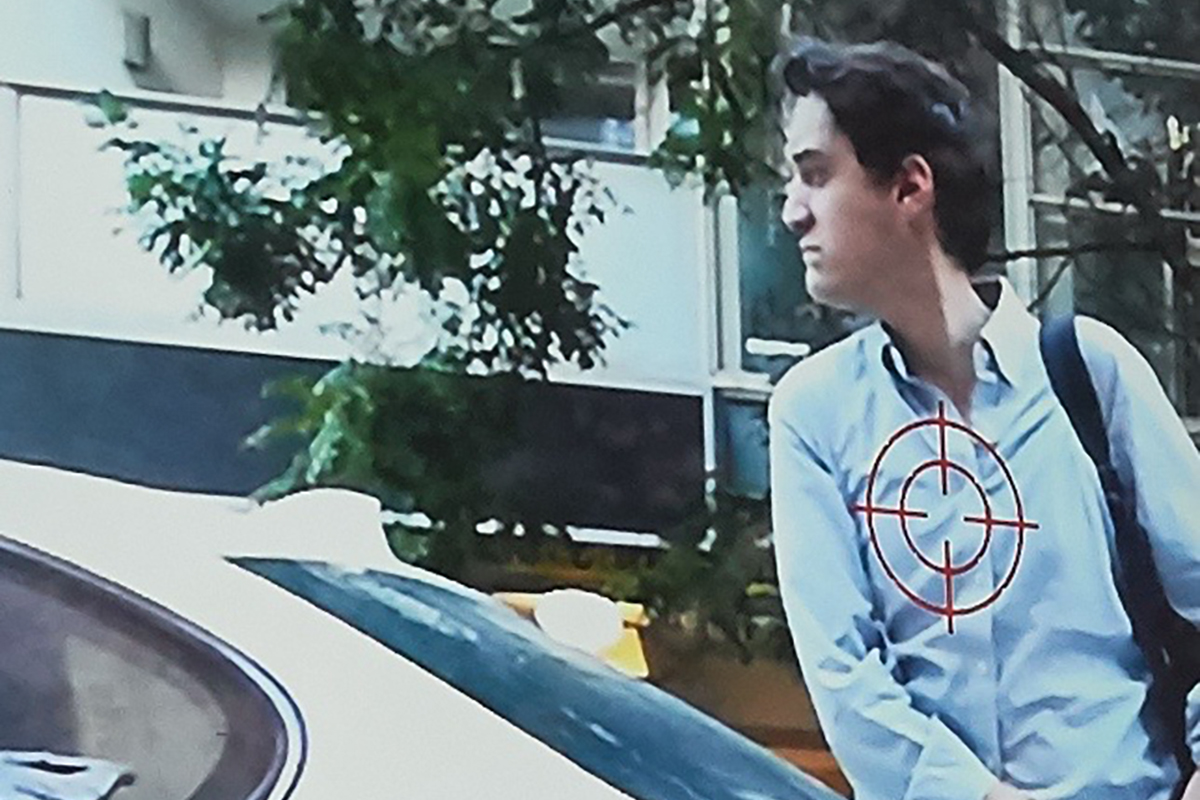

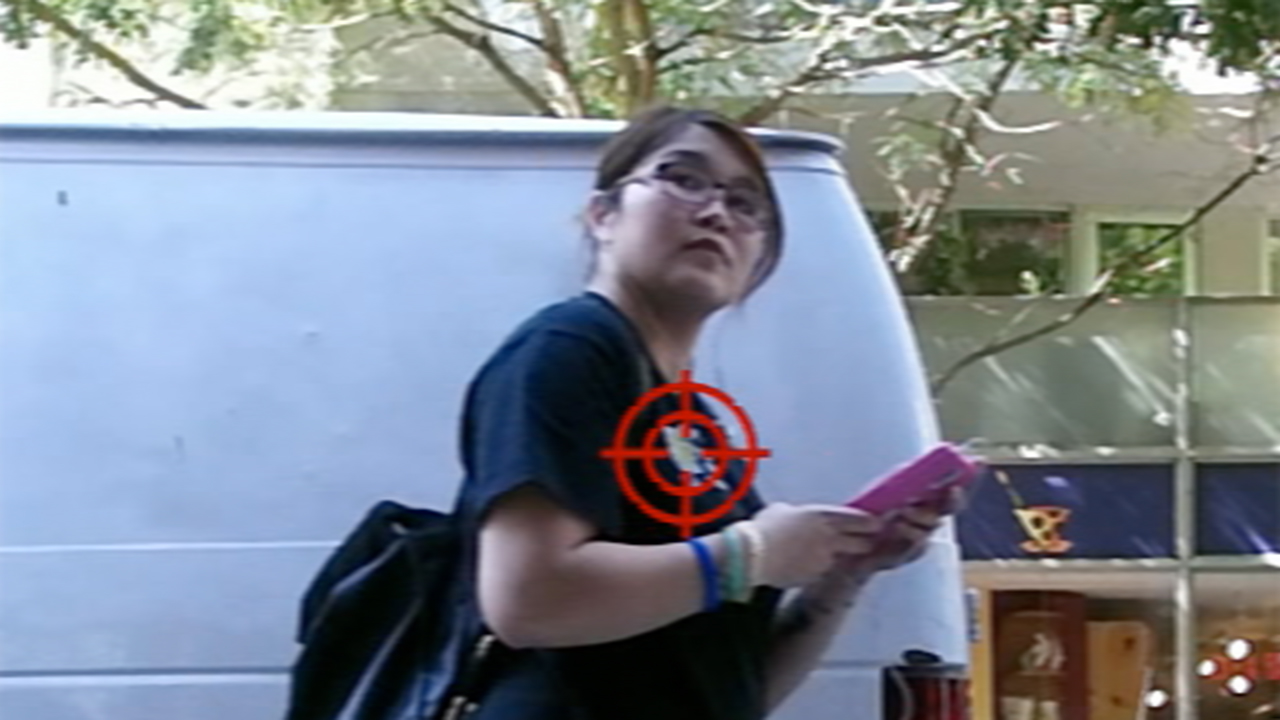

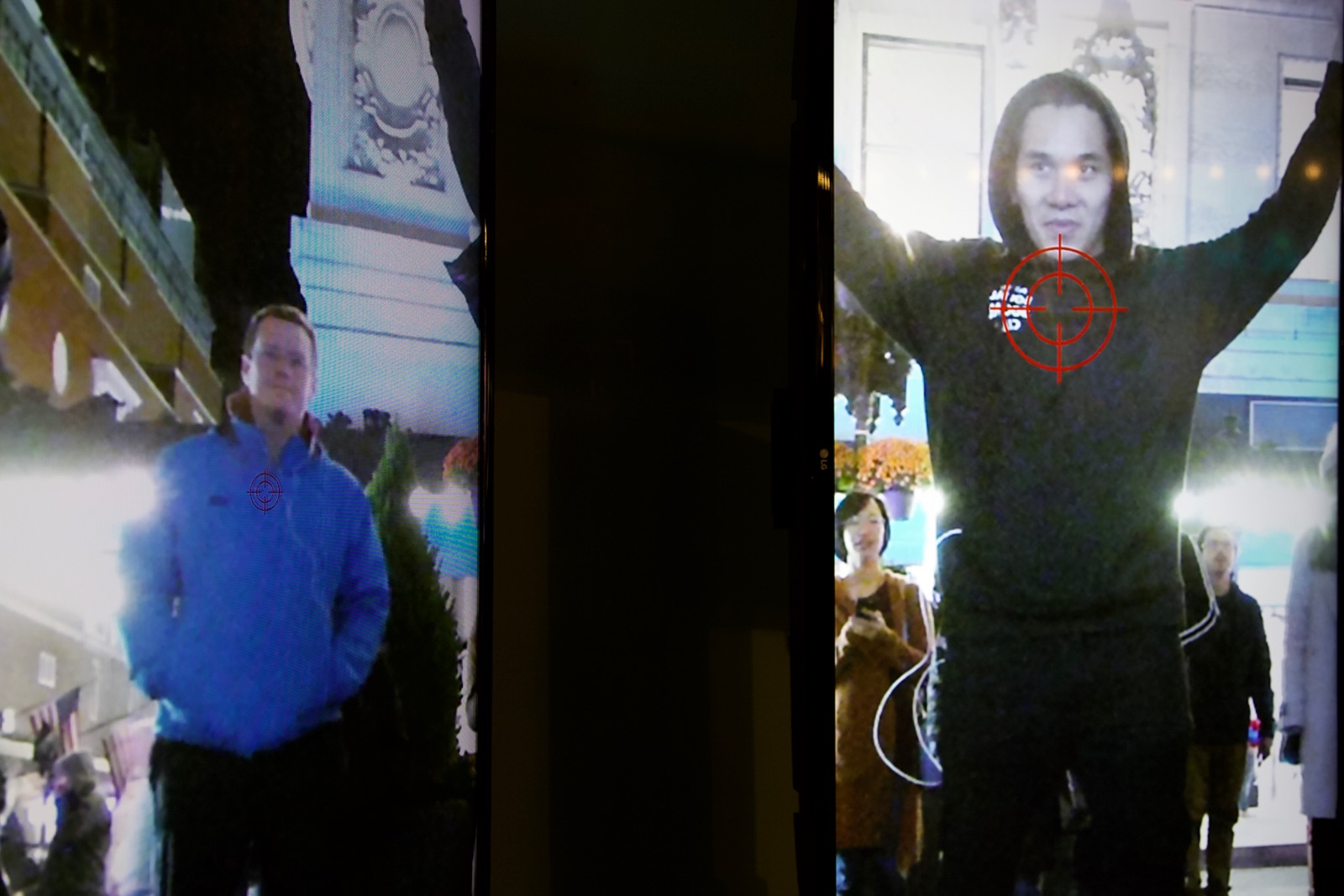

This two-channel interactive video installation has components both outside and inside the gallery. Outside the gallery, which is to say, on the street, speakers blurt out police scanner audio as people walk by. When the viewer turns towards the gallery windows, they see video of themselves with a target sign affixed to their chest.

Inside the gallery is a monitor that shows a live feed of the people being targeted outside, which effectively transforms the viewer from the one who is targeted into one who surveils others being targeted.

Targeted debuted in POLARIS, a group show curated by Joey Lico at the Camera Club of New York (126 Baxter St) that ran from September 7 until October 15, 2016 . It measures 5' × 6'.

The accompanying audio is taken from NYPD scanners in precincts 1, 5, and 7 in Manhattan (Chinatown, SoHo, Little Italy, Lower East Side, Tribeca, World Trade Center, and Financial District) and precincts 72, 76, and 78 in Brooklyn (Red Hook, Carroll Gardens, Park Slope, Greenwood and Sunset Park). This piece measures 8' × 4' and is built with OpenFrameworks and uses an open‑source library by Elliot Woods.

Shown for the first time at one of New York’s oldest art institutions, the Camera Club of New York, Targeted is the institution’s first interactive artwork in its 132‑year history.

Susquehanna University, 2017

Photographs derived from the original installation in Chinatown (NYC) were exhibited in Photography as Social Conscience: Impassioned Portrayals of Race in the United States, a national photography exhibition judged by Ceaphas Stubbs. Prints are life-size measuring 36"x72" and are affixed directly to the wall with staples.

From left to right in the slideshow above: Targeted 2016‑09‑15 14:35:09, Targeted 2016‑09‑15 13:45:58, Targeted 2016‑09‑15 13:58:49. This show took place at the Lore Degenstein Gallery of Susquehanna University from January 28 to March 5, 2017.

Real Art Ways (2017)

Targeted was shown in the group show Nothing To Hide? Art, Surveillance, and Privacy at Real Art Ways. This show also featured work by Trevor Paglen, Rafael Lozano‑Hemmer, Eva and Franco Mattes, and Julian Oliver.

Illunimus Boston (2018)

In 2018 Targeted was shown as part of Illuminus Boston, a nighttime art installation festival in the heart of downtown Boston.

Artist Statement

In the summer of 2016, the day after Philando Castile and Alton Sterling were shot by police, I had an appointment with a curator to discuss the creation of a new interactive work for an upcoming exhibition. The blank slate with which I normally approach site-specific projects was no longer possible.

This project aims to provide a framework for those who are not routinely targeted to feel what it’s like, if only for a moment, to be targeted while innocent. That said, as I was developing the work I became keenly aware that this piece would also target those who are routinely targeted, namely African Americans and other minorities.

Regardless of my intentions, I didn’t want my work to do more harm than good. So, I sought counsel from BIPOC friends, colleagues, and those in the art world. Specifically, I would ask, “on a scale of 1—10, how bad is this?” hoping to leave room for people to feel at ease in expressing their potentially negative feelings or feedback.

To my relief, none of the individuals I asked, nor (to my knowledge) the thousands of people from many different walks of life who saw the piece first-hand in New York City, Hartford, Susquehanna (PA), and Boston, found the work objectionable or offensive.

When I give talks about this piece, I try to take its criticisms head-on, and the one I hear most often goes, “Another White artist profiting from the suffering of African Americans and other minorities.” Of course I have to acknowledge there is a long, well-documented history of exactly that happening for centuries across all layers of American society, so it comes from a valid place.

To address the criticism, I can confidently say I didn’t profit financially nor professionally from this work. Like all my video installations, the work was created without any intention or expectation of financial profit. In fact, if history were to be a guide, I fully expected to lose money on this installation, which is indeed what happened (for those familiar with the art world, this is not surprising). While I received an honorarium of $500 from the Camera Club of New York, I spent nearly twice as much on supplies and technology. The only time I had the potential to profit financially (from a potential juried award at Susquehanna University), I promised to donate the proceeds to Black Lives Matter, however, the work was not chosen for award, nor did it garner any press, nor did I reach out to any journalists or media publications to promote the work.

To make art about race in America is to willingly step into a minefield. While others will certainly disagree, I believe it is better to face it and try to make one’s way through rather than walk around.